| Виртуальный Владимир » Город Владимир » Old Russian Towns » Yuryev-Polskoi » Historic Buildings » Cathedral of St. Cathedral of St. George » history |

...

... history

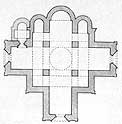

history Let us resist the temptation to pass straight on to the carving, and examine the cathedral's architectural composition. It is a very small building and retains the dimensions of the original church of Suzdal cathedral its side walls were adjoined by vaulted narthexes with a pointed zakomara on the outer wall and flat pilaster strips on the corners. The west narthex was larger and higher than the two side ones, as was also the case in the Suzdal cathedral. It had an upper storey where the prince's family stood during services (we do not yet know how they had access to this storey). In the corner between the north wall of the cathedral and the east wall of the north narthex there was the small Trinity Chapel, the burial vault of the Yuryev princes. In the outer north wall of the cathedral one can still see the niche where Prince Svyatoslav was buried in 1252. In the east wall of the narthex there is a blocked-up door which once led into the burial vault. Excavations have shown that the chapel was a very small one with a single apse and an interior measuring (1,80X3,50 м). Thus the overall composition of the cathedral was asymmetrical.

Let us resist the temptation to pass straight on to the carving, and examine the cathedral's architectural composition. It is a very small building and retains the dimensions of the original church of Suzdal cathedral its side walls were adjoined by vaulted narthexes with a pointed zakomara on the outer wall and flat pilaster strips on the corners. The west narthex was larger and higher than the two side ones, as was also the case in the Suzdal cathedral. It had an upper storey where the prince's family stood during services (we do not yet know how they had access to this storey). In the corner between the north wall of the cathedral and the east wall of the north narthex there was the small Trinity Chapel, the burial vault of the Yuryev princes. In the outer north wall of the cathedral one can still see the niche where Prince Svyatoslav was buried in 1252. In the east wall of the narthex there is a blocked-up door which once led into the burial vault. Excavations have shown that the chapel was a very small one with a single apse and an interior measuring (1,80X3,50 м). Thus the overall composition of the cathedral was asymmetrical.

The cathedral's outer walls were divided vertically into three sections by pilasters and horizontally by a band of blind arcading, part of which survived after the building collapsed in the fifteenth century. The band also ran along the tops of the apses which were divided by semi-columns. Above the band one must imagine the upper part of the walls ending in ogee-shaped zakomams. There were long, narrow windows in both the lower and upper section of the walls. Directly above the centre of the square main body of the cathedral rose the dome proudly elevated on a special base. It was this heavy load which caused the vaulting to collapse in the fifteenth century. Thus we can see that the proportions of the original building were extremely slender and dynamic. The solid heaviness of the present building is the result of Yermolin's restoration work.

The cathedral's outer walls were divided vertically into three sections by pilasters and horizontally by a band of blind arcading, part of which survived after the building collapsed in the fifteenth century. The band also ran along the tops of the apses which were divided by semi-columns. Above the band one must imagine the upper part of the walls ending in ogee-shaped zakomams. There were long, narrow windows in both the lower and upper section of the walls. Directly above the centre of the square main body of the cathedral rose the dome proudly elevated on a special base. It was this heavy load which caused the vaulting to collapse in the fifteenth century. Thus we can see that the proportions of the original building were extremely slender and dynamic. The solid heaviness of the present building is the result of Yermolin's restoration work.

The cathedral's interior is equally unusual. It creates an impression of spaciousness in spite of its small dimensions. The square, non-cruciform pillars are placed wide apart and the walls are without pilaster strips. This gives the interior an almost hall-like appearance, an impression which is reinforced by the absence of a choir-gallery. The west wall contains an archway which led into the upper storey of the narthex; this section took the place of a choir-gallery for the royal family. The main body of the cathedral merged in with the altar area, divided off by a low screen with a carved Deesis, and the open narthexes which increased the impression of size. The small low interiors of the narthexes contrasted strongly with the high, open, main body. During his restoration of the cathedral Yermolin added tiered supporting arches under the dome drum. A similar system linked with tiered roofs already existed in Russian architecture at the beginning of the thirteenth century, so it is possible that Yermolin was copying the original structure. It enhanced the centricity, height and space of the interior. The white stone portal of the entrance into the burial vault, which was restored by Yermolin, still remains on the east wall of the north narthex. Its rich moulding is almost Gothic in character. The interior of the cathedral was well lit by two rows of long, narrow windows so that it lacked the austere gloom typical of twelfth-century churches like the one in Kideksha.

The cathedral's interior is equally unusual. It creates an impression of spaciousness in spite of its small dimensions. The square, non-cruciform pillars are placed wide apart and the walls are without pilaster strips. This gives the interior an almost hall-like appearance, an impression which is reinforced by the absence of a choir-gallery. The west wall contains an archway which led into the upper storey of the narthex; this section took the place of a choir-gallery for the royal family. The main body of the cathedral merged in with the altar area, divided off by a low screen with a carved Deesis, and the open narthexes which increased the impression of size. The small low interiors of the narthexes contrasted strongly with the high, open, main body. During his restoration of the cathedral Yermolin added tiered supporting arches under the dome drum. A similar system linked with tiered roofs already existed in Russian architecture at the beginning of the thirteenth century, so it is possible that Yermolin was copying the original structure. It enhanced the centricity, height and space of the interior. The white stone portal of the entrance into the burial vault, which was restored by Yermolin, still remains on the east wall of the north narthex. Its rich moulding is almost Gothic in character. The interior of the cathedral was well lit by two rows of long, narrow windows so that it lacked the austere gloom typical of twelfth-century churches like the one in Kideksha.

All these features show the rapid and profound changes that had taken place in the Vladimir-Suzdalian school of architecture. They are most strikingly apparent, however, in the amazingly beautiful and unusual decoration of the cathedral.

It is easy to distinguish which part of the building remained intact after some of it collapsed in the fifteenth century and which parts were added later by Yermolin. The line runs diagonally from the upper northwest corner to the lower southeast section. The part which survived best of all is the north wall where even the band of blind arcading remained intact and the adjoining section of the west wall. As we have already mentioned, the west narthex lost its upper storey. All that remained of the south wall were some small sections connected with the narthex. At the corners of the south wall only the old socle survived, as in the case of the apses. Above this line the walls were restored by Yermolin. One must give him credit for having treated the carving with such respect. He could easily have removed it altogether because the taste for decorating church exteriors with carving was already a thing of the past in the fifteenth century. The architect was obviously fascinated by the beauty of the old carving, however, and studied it carefully. Wherever he saw a link between the different pieces he joined them together. On the west section of the south wall, for example, he placed together two stones depicting the Trinity, several stones with lions' heads and human faces intertwined with garlands, and some figures of saints from the band of blind arcading which he arranged in a row under the cornice. Obviously he could not possibly put all the pieces back in their original positions - there were no designs or drawings of the old building and many of the pieces of carving had split and were used as part of the masonry. All that Yermolin could do, therefore, was to face the walls with the pieces of carving that were left without any kind of order turning the cathedral into a kind of stone puzzle. More than eighty complete carved stones were used by Yermolin to build the new vaults and are now hidden under the roof. Others which found their way into neighbouring houses and new buildings later demolished have been collected together by Pyotr Baranovsky and are now inside the cathedral.

It is easy to distinguish which part of the building remained intact after some of it collapsed in the fifteenth century and which parts were added later by Yermolin. The line runs diagonally from the upper northwest corner to the lower southeast section. The part which survived best of all is the north wall where even the band of blind arcading remained intact and the adjoining section of the west wall. As we have already mentioned, the west narthex lost its upper storey. All that remained of the south wall were some small sections connected with the narthex. At the corners of the south wall only the old socle survived, as in the case of the apses. Above this line the walls were restored by Yermolin. One must give him credit for having treated the carving with such respect. He could easily have removed it altogether because the taste for decorating church exteriors with carving was already a thing of the past in the fifteenth century. The architect was obviously fascinated by the beauty of the old carving, however, and studied it carefully. Wherever he saw a link between the different pieces he joined them together. On the west section of the south wall, for example, he placed together two stones depicting the Trinity, several stones with lions' heads and human faces intertwined with garlands, and some figures of saints from the band of blind arcading which he arranged in a row under the cornice. Obviously he could not possibly put all the pieces back in their original positions - there were no designs or drawings of the old building and many of the pieces of carving had split and were used as part of the masonry. All that Yermolin could do, therefore, was to face the walls with the pieces of carving that were left without any kind of order turning the cathedral into a kind of stone puzzle. More than eighty complete carved stones were used by Yermolin to build the new vaults and are now hidden under the roof. Others which found their way into neighbouring houses and new buildings later demolished have been collected together by Pyotr Baranovsky and are now inside the cathedral.

This valuable collection of thirteenth-century sculpture deserves special attention. It includes the Crucifixion and the stone inscription accompanying Svyato-slav's Cross saying that the latter had been laid by Prince Svyatoslav, the cathedral's builder. Here we can also see a fragment of Alexander the Great ascending to Heaven (a composition which we have already seen in the Vladimir churches), a Deesis with five figures which used to stand above the cathedral's west portal, a series of small semi-circular or ogee-shaped stones with oriental-type heads and busts, female masks with elaborate coiffures crowned with head-dresses, fragments of ornaments and architectural parts and so on.

This valuable collection of thirteenth-century sculpture deserves special attention. It includes the Crucifixion and the stone inscription accompanying Svyato-slav's Cross saying that the latter had been laid by Prince Svyatoslav, the cathedral's builder. Here we can also see a fragment of Alexander the Great ascending to Heaven (a composition which we have already seen in the Vladimir churches), a Deesis with five figures which used to stand above the cathedral's west portal, a series of small semi-circular or ogee-shaped stones with oriental-type heads and busts, female masks with elaborate coiffures crowned with head-dresses, fragments of ornaments and architectural parts and so on.

Оставить комментарий:

Виртуальный Владимир

Виртуальный Владимир Область

Область Панорамы города

Панорамы города Организации

Организации Улицы и дома

Улицы и дома Добавить организацию

Добавить организацию О городе

О городе