| Виртуальный Владимир » Город Владимир » Old Russian Towns » Vladimir » Historic buildings » Cathedral of the Assumption |

The Cathedral of the Assumption was the largest building in Andrei Bogolyubsky's new capital and became the focal point of the town's architectural ensemble and its southern aspect. From its excellent vantage point it seemed to dominate the whole of the town and its broad surroundings. Its golden dome was visible from the distant wooded heights along which lay the road to Murom. The very position of the Cathedral, standing boldly on the edge of the town, emphasises the importance of its role, namely, to affirm the independence of the Vladimir lands and the ambitious political and ecclesiastical pretensions of the prince and bishop of Vladimir. The new cathedral stood guard over the steep approaches to the town like a giant warrior in a golden helmet.

The Cathedral of the Assumption was the largest building in Andrei Bogolyubsky's new capital and became the focal point of the town's architectural ensemble and its southern aspect. From its excellent vantage point it seemed to dominate the whole of the town and its broad surroundings. Its golden dome was visible from the distant wooded heights along which lay the road to Murom. The very position of the Cathedral, standing boldly on the edge of the town, emphasises the importance of its role, namely, to affirm the independence of the Vladimir lands and the ambitious political and ecclesiastical pretensions of the prince and bishop of Vladimir. The new cathedral stood guard over the steep approaches to the town like a giant warrior in a golden helmet.

The foundations of the cathedral were laid in 1158 at the same time as work was begun on the erection of huge defensive ramparts round the town. The chronicles tell us that Prince Andrei intended it to be not only the main cathedral of the Vladimir bishopric, but a demonstration that the Vladimir Metropolitan was independent of the ecclesiastical authorities in Kiev. Vladimir was claiming to be the "supreme head", i.e., the political centre of feudal Russia. This inevitably involved the question of ecclesiastical supremacy as well. The church extended its authority throughout the separate feudal principalities as a constant reminder of Russian unity at a time when the country was riven by internecine feuds.

The foundations of the cathedral were laid in 1158 at the same time as work was begun on the erection of huge defensive ramparts round the town. The chronicles tell us that Prince Andrei intended it to be not only the main cathedral of the Vladimir bishopric, but a demonstration that the Vladimir Metropolitan was independent of the ecclesiastical authorities in Kiev. Vladimir was claiming to be the "supreme head", i.e., the political centre of feudal Russia. This inevitably involved the question of ecclesiastical supremacy as well. The church extended its authority throughout the separate feudal principalities as a constant reminder of Russian unity at a time when the country was riven by internecine feuds.

The local builders and craftsmen who had acquired their skills during the reign of Yuri Dolgoruky were too few in number to carry out the ambitious plans for building the new capital, particularly the Cathedral of the Assumption, and the chronicle tells us that "God brought artists to Andrei from all parts of the earth". These did not, however, include master brick layers from Kiev and the towns of the Dnieper Basin. They were expert stone masons, including Romanesque craftsmen from the West who are said to have been sent to Andrei by Barbarossa. In the Europe of the Middle Ages it was quite usual to gather craftsmen from various different countries to erect buildings of some importance. It was particularly significant in the case of Vladimir, whose striving to consolidate its independence and establish its authority over all the Russian lands inevitably brought it into conflict with Kiev and the Kiev Metropolitan. The use of Western craftsmen was, to a certain extent, an open refusal to rely on help from Kiev and Kievan architectural and artistic traditions. Like his famous ancestor Vladimir I, the "baptiser" of Russia, whom Andrei strove to emulate, the prince endowed the new cathedral, which was completed in 1160, with extensive lands and set aside a tenth of his revenue for its upkeep. Thus the Vladimir cathedral became a "tithe" foundation, like the old Church of the Dime (Desyatinnaya Tserkov) in Kiev.

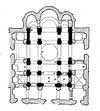

The present building dates back to two separate periods. The cathedral erected by Andrei was severely damaged in the fire of 1185 when its wooden supports were destroyed and the white limestone of the walls was badly burnt, making it difficult to restore the building to its original form. The architects of Vsevolod III therefore decided to surround the structure with new walls or galleries (1185-1189), strengthening the old ones with pillars and connecting them to the new walls with arches. Thus the old building was encased, as it were, in a new one (111. 6). Large and small arched openings were cut in the walls of the old building forming rows of pillars in the enlarged cathedral which also had three new apses.

The subsequent events in the history of this magnificent building are also of importance. When the Mongols captured the town in 1238 they stacked up wood against the exterior and interior of the cathedral and set fire to it, with the prince's family, the bishop, and some of the townspeople in the choir-gallery. The building remained standing, however, and at the end of the thirteenth century it was given another tin roof and a new brick Chapel of St. Panteleimon was added in the southwest corner, which has not survived. In 1410 the town was attacked by the Mongols for the last time, when they "did ravage the gold-domed church" as the chronicle puts it. There is also mention of the priceless church-plate being concealed in a secret hiding-place inside the cathedral. The building was again damaged by fire in 1536. By the eighteenth century it was in a very dilapidated condition, with numerous long cracks in the walls and arches. It was then repaired with a new hipped roof and many other alterations which spoilt its original appearance. In 1862 the heated, brick Chapel of St. George was built between the bell-tower and north wall of the cathedral. It was not until the restoration work carried out in 1888-1891 that the cathedral regained its original appearance (111. 7). However, a large section of the outer walls was re-faced with new stone, part of the weathered stone carving was replaced, and a new nar-thex was built on the west side. Restoration work has re¬vealed the same excellent technical features which we observed in our study of the Golden Gates: the fine finish of the stone and masonry and the use of a lighter material, porous tufa, for the vaulting and domes of the cathedral.

Let us now go into the cathedral and stand for a while in its west gallery. Before us is the west wall of the old cathedral intersected with large arches. On a level with the choir-gallery there is an ornamental frieze consisting ot a band of blind arcading, with slender columns wedge-shaped consoles, cube-like capitals of Romanesque type, and a line of vertically set stone over the blind arcading. This type of ornament can be traced throughout all the subsequent building in Vladimir and Suzdal and later appears in Moscow architecture. The structure of the wall determined the position of the band The section of the wall below the band is thicker. Above the band it becomes thinner forming a drip mould above the line of vertically set stone. In the upper section of the wall on either side there are graceful slit windows with indented jambs. Walking through to the northern gallery we see the same picture. He're between the slender columns of the blind arcading there are small windows which originally formed the lower tier of lighting. Consequently the old cathedral must have been very light inside. There is also an extremely rare fragment of the frescoes which were painted on the outer walls in 1161. Two blue peacocks with magnificent tails stand above the narrow slit window on either side of which there is a graceful foliate design. The spaces to the right and left of the columns are filled with the fig¬ures of two prophets with scrolls in their hands. The columns were originally covered with gold. Thus the gleaming white walls of the old cathedral had a rich band of colour running round them. This fresco band foreshadowed the later appearance of a strip of orna¬mental carving.

Let us now go into the cathedral and stand for a while in its west gallery. Before us is the west wall of the old cathedral intersected with large arches. On a level with the choir-gallery there is an ornamental frieze consisting ot a band of blind arcading, with slender columns wedge-shaped consoles, cube-like capitals of Romanesque type, and a line of vertically set stone over the blind arcading. This type of ornament can be traced throughout all the subsequent building in Vladimir and Suzdal and later appears in Moscow architecture. The structure of the wall determined the position of the band The section of the wall below the band is thicker. Above the band it becomes thinner forming a drip mould above the line of vertically set stone. In the upper section of the wall on either side there are graceful slit windows with indented jambs. Walking through to the northern gallery we see the same picture. He're between the slender columns of the blind arcading there are small windows which originally formed the lower tier of lighting. Consequently the old cathedral must have been very light inside. There is also an extremely rare fragment of the frescoes which were painted on the outer walls in 1161. Two blue peacocks with magnificent tails stand above the narrow slit window on either side of which there is a graceful foliate design. The spaces to the right and left of the columns are filled with the fig¬ures of two prophets with scrolls in their hands. The columns were originally covered with gold. Thus the gleaming white walls of the old cathedral had a rich band of colour running round them. This fresco band foreshadowed the later appearance of a strip of orna¬mental carving.

In place of the large openings in the middle of the north, west and south walls of the old cathedral one must imagine deeply recessed portals leading into the body of the church. These portals contained the precious "golden gates" covered with damascened copper sheets, similar to those which we shall see in the Suzdal cathe¬dral (Ills. 66-69). The portals themselves were also covered with thin sheets of gilded copper. Excavation work on the floor of the north gallery has revealed that there were small vaulted narthexes adjoining the portals. Traces of the articulating pilasters on the outer walls of the old cathedral can be seen here and there under the pillars of the gallery adjoining the old walls. The upper section of the old walls topped with rounded zakomaras* and the rich foliate capitals of the pilasters can also be seen above the vaulting of the gallery. There was a little carving on the zakomaras and round the windows, part of which were later transferred to the outside of the new walls. In the central zakomaras there were large compositions depicting such scenes as the Ascension oi Alexander the Great, the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste and the Three Youths in the Fiery Furnace. Below these were carved female masks, a sign that the cathedral was dedicated to Our Lady, and animal masks at the corners of the windows. The simplicity of the carving emphasised the slender, elegant lines of the building. We shall observe a similar restrained use of carved decoration in the Church of the Intercession on the Nerl. Carved birds and vessels of gilded copper were placed above the zakomaras. The drum of the cathedral's single helmet-shaped golden dome was decorated with a band of blind arcading with semi-columns and sheets of gilded copper and stood on a square base rising above the vaulted roof.

In place of the large openings in the middle of the north, west and south walls of the old cathedral one must imagine deeply recessed portals leading into the body of the church. These portals contained the precious "golden gates" covered with damascened copper sheets, similar to those which we shall see in the Suzdal cathe¬dral (Ills. 66-69). The portals themselves were also covered with thin sheets of gilded copper. Excavation work on the floor of the north gallery has revealed that there were small vaulted narthexes adjoining the portals. Traces of the articulating pilasters on the outer walls of the old cathedral can be seen here and there under the pillars of the gallery adjoining the old walls. The upper section of the old walls topped with rounded zakomaras* and the rich foliate capitals of the pilasters can also be seen above the vaulting of the gallery. There was a little carving on the zakomaras and round the windows, part of which were later transferred to the outside of the new walls. In the central zakomaras there were large compositions depicting such scenes as the Ascension oi Alexander the Great, the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste and the Three Youths in the Fiery Furnace. Below these were carved female masks, a sign that the cathedral was dedicated to Our Lady, and animal masks at the corners of the windows. The simplicity of the carving emphasised the slender, elegant lines of the building. We shall observe a similar restrained use of carved decoration in the Church of the Intercession on the Nerl. Carved birds and vessels of gilded copper were placed above the zakomaras. The drum of the cathedral's single helmet-shaped golden dome was decorated with a band of blind arcading with semi-columns and sheets of gilded copper and stood on a square base rising above the vaulted roof.

Let us now enter the old cathedral and stand under its dome. The light spacious interior of the building im¬presses one, first and foremost, by its height. And the cathedral did in fact rival in height the greatest building of its time in old Russia, the Cathedral of St. Sophia in Kiev. This was obviously intentional, since Prince Andrei could not allow his new cathedral to be less impressive than the one in Kiev. The area which it covered was less, however, and this made its height all the more striking. Moreover, the architects reinforced this impression by the comparative lightness of the six graceful cruciform pillars which appeared to support the cathedral's vaulted roof and single dome without the slightest effort. The light from the dome's twelve windows created the impression that the enormous head of Christ painted on the inside of the dome was rising into the heavens. The construction of the base of the dome is interesting. The builders used the unusual technique of introducing eight small supplementary pendentives between the large corner ones, thus effecting a smooth transition from the square of supporting arches to the circular drum. The general impression of lightness and height was reinforced by the bold use of carving. At the impost of the arches there are pairs of lions couchant carved in high relief with an absence of intricate detail, evidently because of their foreshortened appearance when seen from below. On the other hand, the bands of shallow carved ornament under the choir-gallery opposite contain the most graphic detail. Everything, from the building as a whole down to the smallest section, bears witness to the remarkable skill and taste of the architects.

The most important position on the screen, to the left of the Holy Doors, was occupied by the principality's most cherished sacred possession - the icon of Our Lady of Vladimir which Andrei Bogolyubsky had transferred from Kiev to Vladimir in 1167. This icon, which can now be seen in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, was the work of an extremely gifted Byzantine master and shows a degree of lyrical emotion quite unusual for its date (111. 13). Instead of the usual proud, stylised "Queen of the Heavens" the painter has represented the tender figure of a young mother with a delicate, oval face and eyes which radiate love for her child and sad¬ness at the fate which awaits him. This icon, so full of human warmth, must have made an extremely powerful impression on people at that time. The prince had it lavishly decorated with gold, silver and precious stones.

The chronicle tells us that during the feast of the Assumption the golden gates of the south and north portals were opened and between them, on two "wondrous cords" were hung the sumptuous vestments and other rich cloths donated to the cathedral by the princes. Along this corridor of precious, brightly coloured cloth which continued outside the cathedral as well, swaying slightly in the breeze, a stream of townspeople and peasants came to pay homage to the icon. The rich majolica tiled floor of the cathedral spread out under their feet like a shining carpet. The cathedral's splendour was enhanced by the sumptuous plate inside it, Mikula, the prince's spiritual advisor, describes the decorations as follows: "Prince Andrei ... did build the wondrously fair Church of Our Lady and did adorn it with divers objects of gold and silver, building three golden gates and ornamenting the church with precious stones, pearls and many wondrous patterns. He did light the church with many silver and gold chandeliers and censers and did build an ambo of gold and silver. The church did possess much gold church-plate, flabella, and other holy objects studded with precious stones and pearl . . . Thus the Church of Our Lady was as wondrous fair as the very Temple of Solomon". One can well imagine the powerful impression which this scene made on the worshippers who had come from their crude peasant huts and cramped town dwellings.

The chronicle tells us that during the feast of the Assumption the golden gates of the south and north portals were opened and between them, on two "wondrous cords" were hung the sumptuous vestments and other rich cloths donated to the cathedral by the princes. Along this corridor of precious, brightly coloured cloth which continued outside the cathedral as well, swaying slightly in the breeze, a stream of townspeople and peasants came to pay homage to the icon. The rich majolica tiled floor of the cathedral spread out under their feet like a shining carpet. The cathedral's splendour was enhanced by the sumptuous plate inside it, Mikula, the prince's spiritual advisor, describes the decorations as follows: "Prince Andrei ... did build the wondrously fair Church of Our Lady and did adorn it with divers objects of gold and silver, building three golden gates and ornamenting the church with precious stones, pearls and many wondrous patterns. He did light the church with many silver and gold chandeliers and censers and did build an ambo of gold and silver. The church did possess much gold church-plate, flabella, and other holy objects studded with precious stones and pearl . . . Thus the Church of Our Lady was as wondrous fair as the very Temple of Solomon". One can well imagine the powerful impression which this scene made on the worshippers who had come from their crude peasant huts and cramped town dwellings.

Their blind faith in the miraculous power of the divine, particularly in the icon of Our Lady of Vladimir, played an important part in the Vladimir princes' bitter political struggle for overlordship of all the Russian lands, in the struggle of the townspeople for the inde¬pendence of Vladimir, and the attempts of the boyars to gain control of the town. At the same time the flourishing arts served to enhance the authority of the princes and the church.

During a service the prince and his entourage were to be found in the choir-gallery at the west end of the cathedral, from which they had an excellent view of the whole interior and the ritual taking place at the altar. This division in the church's interior, typical of early Russian architecture, was a strikingly concrete reflection of the main division in the feudal hierarchy: the prince and nobility were actually placed above the heads of the ordinary people in the church. This idea was emphasised even further by the large fresco of the Last Judgment, one of the most important in the strictly prescribed se¬quence of religious scenes with which Russian churches were decorated, which was placed under the choir-gallery and served to remind the congregation of the allegiance they owed to God and their earthly masters, and of the terrible retribution awaiting sinners in the next world.

During a service the prince and his entourage were to be found in the choir-gallery at the west end of the cathedral, from which they had an excellent view of the whole interior and the ritual taking place at the altar. This division in the church's interior, typical of early Russian architecture, was a strikingly concrete reflection of the main division in the feudal hierarchy: the prince and nobility were actually placed above the heads of the ordinary people in the church. This idea was emphasised even further by the large fresco of the Last Judgment, one of the most important in the strictly prescribed se¬quence of religious scenes with which Russian churches were decorated, which was placed under the choir-gallery and served to remind the congregation of the allegiance they owed to God and their earthly masters, and of the terrible retribution awaiting sinners in the next world.

There was also a special entrance leading to the choir-gallery. Two arched openings can still be seen in the walls, which now lead from the gallery to small platforms standing on the cross-vaulting above the galleries built by Vsevolod. A new spiral staircase has been built up to the old choir-gallery. We do not know exactly what the original entrance looked like. The chronicles mention buildings that were linked with the cathedral, such as the entrance passage of the bishop's residence and, it appears, the royal chambers. Excavations in the northern gallery near the northern entrance to the choir-gallery have revealed the foundations of a building connected to the cathedral by a narrow passage. It is possible that these are, in fact, the remains of the bishop's residence, the first floor of which would also have been connected with the choir-gallery by another passage. It is most likely that this was matched on the south side by a wing of the royal chambers also connected directly with the gallery.

The erection of galleries round the cathedral turned it into a new, even larger building. In place of the old apses three new ones were built considerably further east. Although new openings were made in the walls of the old cathedral the building did not take on the form of a church with eighteen pillars and five aisles. The distinction between the old cathedral and the new galleries was quite obvious inside the building and was empha¬sised by the building of separate entrances on the west side.

The interior of the old cathedral took on a quite different character. It became darker in spite of the double row of windows which were built in the south wall of the gallery and the four new windowed domes above the galleries. The galleries themselves with their solid arched cross-pieces were also dark. They were intended to serve as a burial place for the princes and church dignitaries of Vladimir, and special arched niches for the white stone sarcophagi were built into the walls. A sarcophagus containing the remains of Prince Andrei, the cathedral's founder, was transferred from its original resting place to the northeast corner of the galleries. By the opposite wall stood the coffin of his brother and successor, Vsevolod III, who had given the old cathedral a new casing. Other members of the royal family and bishops were subsequently buried in the remaining niches and below the gallery floors. Thus the interior of the old cathedral lost its bright, festive appearance. Its jubilant, majestic atmosphere was replaced by the hushed solemnity of a dark burial vault, the giant mausoleum of the "Vladimir autocrats".

The interior of the old cathedral took on a quite different character. It became darker in spite of the double row of windows which were built in the south wall of the gallery and the four new windowed domes above the galleries. The galleries themselves with their solid arched cross-pieces were also dark. They were intended to serve as a burial place for the princes and church dignitaries of Vladimir, and special arched niches for the white stone sarcophagi were built into the walls. A sarcophagus containing the remains of Prince Andrei, the cathedral's founder, was transferred from its original resting place to the northeast corner of the galleries. By the opposite wall stood the coffin of his brother and successor, Vsevolod III, who had given the old cathedral a new casing. Other members of the royal family and bishops were subsequently buried in the remaining niches and below the gallery floors. Thus the interior of the old cathedral lost its bright, festive appearance. Its jubilant, majestic atmosphere was replaced by the hushed solemnity of a dark burial vault, the giant mausoleum of the "Vladimir autocrats".

A few very precious wall-paintings which were restored in 1918, have survived in the interior of the cathedral. Most of the walls are covered with late nineteenth-century frescoes of no artistic value restored recently by the cathedral priests.

Оставить комментарий:

Виртуальный Владимир

Виртуальный Владимир Область

Область Панорамы города

Панорамы города Организации

Организации Улицы и дома

Улицы и дома Добавить организацию

Добавить организацию О городе

О городе